range(start, stop, step)

range(5) # 0, 1, 2, 3, 4

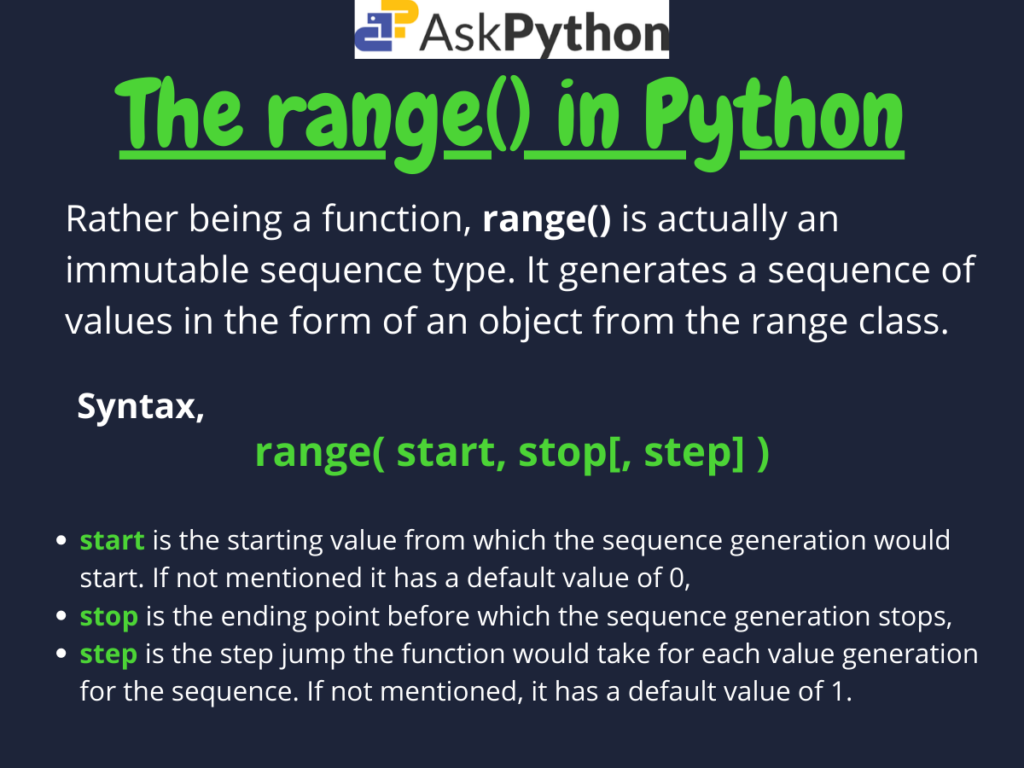

The range() function generates a sequence of numbers that you can iterate over. That’s it. Three parameters, one simple job. You give it boundaries, and it gives you integers within those boundaries.

Most Python developers use range() every single day without thinking about what it actually does under the hood. They slap it into a for loop and move on. But understanding how this function works will save you from some genuinely weird bugs and help you write faster code.

How the Python range function actually works

The range() function doesn’t create a list of numbers. It creates a range object, which is an iterable that generates numbers on demand. This distinction matters because it means you’re not allocating memory for every number in your sequence.

# This doesn't create 1 million integers in memory

big_range = range(1000000)

print(type(big_range)) #

# This does (don't do this)

big_list = list(range(1000000))

When you call range() with a single argument, you get a sequence starting at 0 and ending just before that number. The function always excludes the stop value, which trips up new developers constantly.

for i in range(5):

print(i)

# Outputs: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4

Notice that 5 never appears. You get five numbers total, but they start at zero and stop at four. This zero-indexing matches how Python handles list indices, which makes range() perfect for iterating over list positions.

Using start and stop parameters

The two-parameter version of range() lets you define both the starting point and the stopping point. The sequence begins at your start value and ends just before your stop value.

for num in range(3, 8):

print(num)

# Outputs: 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

You can use this to iterate over specific slices of data or to generate numbers within a particular boundary. The start parameter is inclusive, while the stop parameter remains exclusive.

# Generate years from 2020 to 2024

years = range(2020, 2025)

for year in years:

print(f"Processing data for {year}")

This pattern shows up constantly in data processing tasks where you need to work with sequential values that don’t start at zero.

The step parameter for custom intervals

The third parameter controls the interval between numbers. By default, range() increments by one, but you can specify any integer step value.

# Count by twos

even_numbers = range(0, 10, 2)

for num in even_numbers:

print(num)

# Outputs: 0, 2, 4, 6, 8

# Count by fives

multiples_of_five = range(5, 26, 5)

print(list(multiples_of_five))

# [5, 10, 15, 20, 25]

The step parameter unlocks practical applications like iterating through every other item in a list or generating sequences with specific mathematical properties.

# Process every third element

data = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f', 'g', 'h', 'i']

for i in range(0, len(data), 3):

print(data[i])

# Outputs: a, d, g

Counting backwards with negative steps

Negative step values let you generate descending sequences. This works exactly like you’d expect, but you need to make sure your start value is greater than your stop value.

# Countdown

for num in range(10, 0, -1):

print(num)

# Outputs: 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1

# Reverse through indices

items = ['first', 'second', 'third', 'fourth']

for i in range(len(items) - 1, -1, -1):

print(items[i])

# Outputs: fourth, third, second, first

That second example deserves attention because it shows the correct way to iterate backwards through list indices. You start at len(items) - 1 (the last valid index), stop at -1 (which means you’ll process index 0), and step by -1.

Why range returns an iterable instead of a list

Python 3’s range() returns a range object rather than a list because it’s more memory efficient. The range object calculates each value when you ask for it instead of storing all values in memory simultaneously.

# Memory efficient

for i in range(1000000000):

if i > 5:

break

print(i)

# This would crash most systems

# numbers = list(range(1000000000))

The range object knows its start, stop, and step values, so it can calculate any position in the sequence without generating the entire sequence. This makes it blazing fast for iteration and practically free in terms of memory.

You can still convert a range to a list if you actually need all the values stored in memory, but you should only do this when you genuinely need a list.

# When you actually need a list

number_list = list(range(1, 6))

number_list.append(10) # Now you can modify it

print(number_list) # [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10]

Practical applications in real code

The most common use of range() is iterating a specific number of times when you don’t care about the actual values.

# Retry logic

max_attempts = 3

for attempt in range(max_attempts):

try:

result = risky_operation()

break

except Exception as e:

if attempt == max_attempts - 1:

raise

time.sleep(1)

You’ll also use range() constantly with enumerate() when you need both the index and the value.

# But usually just use enumerate instead

fruits = ['apple', 'banana', 'cherry']

for i, fruit in enumerate(fruits):

print(f"{i}: {fruit}")

For generating test data, range() combined with list comprehensions gives you quick sequences with transformations.

# Generate test cases

test_values = [x * 2 + 1 for x in range(10)]

print(test_values)

# [1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19]

# Create coordinate pairs

coordinates = [(x, y) for x in range(3) for y in range(3)]

print(coordinates)

# [(0, 0), (0, 1), (0, 2), (1, 0), (1, 1), (1, 2), (2, 0), (2, 1), (2, 2)]

Common mistakes developers make with range

The biggest mistake is trying to modify the loop variable inside a range()-based loop and expecting it to affect the iteration.

# This doesn't work how you think

for i in range(5):

print(i)

i = 10 # This does nothing to the loop

# Still outputs: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4

The range object generates the next value regardless of what you do to the loop variable. If you need to skip iterations or jump around, use a while loop instead.

Another common error is forgetting that the stop value is exclusive, leading to off-by-one bugs.

# Wrong: misses the last item

items = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50]

for i in range(len(items) - 1):

print(items[i])

# Outputs: 10, 20, 30, 40 (missing 50)

# Right: includes all items

for i in range(len(items)):

print(items[i])

Checking if values exist in a range

You can use the in operator to check if a number exists in a range object. Python calculates this mathematically instead of iterating through every value, making it extremely fast.

print(50 in range(0, 100)) # True

print(150 in range(0, 100)) # False

# Works with step values too

print(6 in range(0, 10, 2)) # True (0, 2, 4, 6, 8)

print(7 in range(0, 10, 2)) # False

This mathematical check happens in constant time regardless of the range size, which makes it useful for validation logic.

Performance characteristics you should know

Range objects have constant-time lookups for length, indexing, and membership testing. This means checking if a number exists in range(1000000000) takes the same time as checking range(10).

# All of these are O(1) operations

large_range = range(0, 1000000000, 2)

print(len(large_range)) # Instant

print(large_range[500000]) # Instant

print(999999 in large_range) # Instant

The range object calculates these values using math instead of iteration. It knows the formula for any position, so accessing the millionth element takes no longer than accessing the first.

This makes range objects perfect for representing large numeric sequences where you only need to access occasional values or check membership. The memory footprint stays tiny regardless of the range size.

When to use range and when to avoid it

Use range() when you need to iterate a specific number of times, generate numeric sequences, or access elements by index. It’s the right tool for controlled iteration and numeric generation.

Avoid range() when you’re just trying to iterate over a collection. Python gives you direct iteration over lists, strings, and other iterables without needing indices.

# Don't do this

items = ['a', 'b', 'c']

for i in range(len(items)):

print(items[i])

# Do this instead

for item in items:

print(item)

The direct iteration is clearer, faster, and less error-prone. Save range() for situations where you actually need the numeric sequence or the index values.