# Syntax

map(function, iterable1, iterable2, ...)

# Example: Square each number in a list

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

squared = map(lambda x: x**2, numbers)

print(list(squared)) # [1, 4, 9, 16, 25]

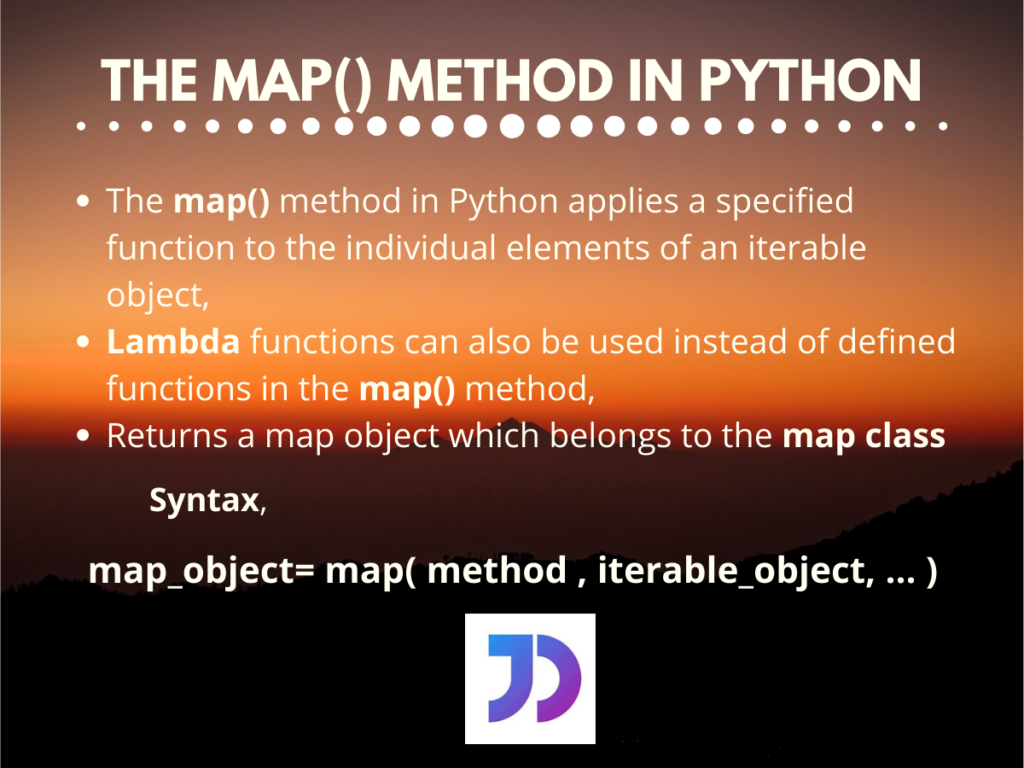

The python map function applies a transformation to every element in an iterable without writing explicit loops. You pass a function and one or more iterables, and map returns an iterator containing transformed values.

Understanding how python map processes data

The map() method takes two required arguments. The first argument accepts any callable function, including built-in functions, lambda expressions, or custom functions. The second argument accepts any iterable object like lists, tuples, strings, or dictionaries.

When you call map(), Python doesn’t immediately process your data. Instead, it returns a map object that computes values only when you request them. This lazy evaluation approach saves memory, particularly when working with large datasets that don’t fit into RAM at once.

def multiply_by_ten(n):

return n * 10

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

result = map(multiply_by_ten, numbers)

print(result) #

The map object generates each transformed value on demand rather than computing all results upfront. Once you iterate through a map object, it becomes exhausted and returns empty results on subsequent iterations.

numbers = [1, 2, 3]

squared = map(lambda x: x**2, numbers)

print(list(squared)) # [1, 4, 9]

print(list(squared)) # [] - exhausted iterator

Using built-in functions with python map

Python’s built-in functions integrate seamlessly with map() for common transformations. You can apply functions like abs(), len(), float(), int(), and str() directly without wrapping them in lambda expressions.

# Convert strings to integers

string_numbers = ['10', '20', '30', '40']

integers = list(map(int, string_numbers))

print(integers) # [10, 20, 30, 40]

# Get absolute values

values = [-5, -2, 0, 3, -8]

absolute = list(map(abs, values))

print(absolute) # [5, 2, 0, 3, 8]

# Calculate string lengths

words = ['python', 'map', 'function', 'tutorial']

lengths = list(map(len, words))

print(lengths) # [6, 3, 8, 8]

String methods work equally well with map(). You can transform entire lists of strings by passing methods like str.upper(), str.lower(), str.strip(), or str.title() directly.

# Convert to uppercase

fruits = ['apple', 'banana', 'cherry']

uppercase = list(map(str.upper, fruits))

print(uppercase) # ['APPLE', 'BANANA', 'CHERRY']

# Remove whitespace

messy_data = [' hello ', ' world ', ' python ']

cleaned = list(map(str.strip, messy_data))

print(cleaned) # ['hello', 'world', 'python']

# Capitalize first letter

names = ['alice', 'bob', 'charlie']

capitalized = list(map(str.capitalize, names))

print(capitalized) # ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie']

Lambda functions unlock python map flexibility

Lambda functions provide inline transformations without defining separate named functions. This approach keeps your code compact when you need simple, one-time operations.

# Calculate squares

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

squares = list(map(lambda x: x**2, numbers))

print(squares) # [1, 4, 9, 16, 25]

# Convert Celsius to Fahrenheit

celsius = [0, 10, 20, 30, 40]

fahrenheit = list(map(lambda c: (c * 9/5) + 32, celsius))

print(fahrenheit) # [32.0, 50.0, 68.0, 86.0, 104.0]

# Extract first character

words = ['python', 'java', 'ruby', 'swift']

initials = list(map(lambda w: w[0], words))

print(initials) # ['p', 'j', 'r', 's']

Lambda functions accept multiple parameters, enabling more complex transformations. You combine this capability with multiple iterables to process corresponding elements together.

# Add corresponding elements

list1 = [1, 2, 3, 4]

list2 = [10, 20, 30, 40]

sums = list(map(lambda x, y: x + y, list1, list2))

print(sums) # [11, 22, 33, 44]

# Calculate product of three lists

a = [2, 3, 4]

b = [5, 6, 7]

c = [1, 2, 3]

products = list(map(lambda x, y, z: x * y * z, a, b, c))

print(products) # [10, 36, 84]

Processing multiple iterables with python map

The python map function accepts multiple iterables as arguments, applying your function to corresponding elements from each iterable simultaneously. This parallel mapping continues until the shortest iterable runs out of elements.

# Raise numbers to powers

bases = [2, 3, 4, 5]

exponents = [1, 2, 3, 4]

results = list(map(pow, bases, exponents))

print(results) # [2, 9, 64, 625]

# Divide corresponding elements

numerators = [10, 20, 30, 40]

denominators = [2, 4, 5, 8]

quotients = list(map(lambda x, y: x / y, numerators, denominators))

print(quotients) # [5.0, 5.0, 6.0, 5.0]

When iterables have different lengths, map() stops processing after exhausting the shortest iterable. No error occurs, and remaining elements from longer iterables simply get ignored.

# Unequal length iterables

short = [1, 2]

long = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50]

result = list(map(lambda x, y: x + y, short, long))

print(result) # [11, 22] - stops after 2 elements

String transformations using python map

String processing tasks become straightforward with map() when you need to apply the same transformation across multiple text elements. This approach shines in data cleaning and text preprocessing workflows.

# Standardize email domains

emails = ['[email protected]', '[email protected]', '[email protected]']

normalized = list(map(str.lower, emails))

print(normalized)

# ['[email protected]', '[email protected]', '[email protected]']

# Add prefixes to identifiers

ids = ['001', '002', '003']

prefixed = list(map(lambda x: f'USER_{x}', ids))

print(prefixed) # ['USER_001', 'USER_002', 'USER_003']

# Extract file extensions

files = ['document.pdf', 'image.png', 'script.py']

extensions = list(map(lambda f: f.split('.')[-1], files))

print(extensions) # ['pdf', 'png', 'py']

Custom string methods combine with map() to handle complex text transformations. You can chain operations inside lambda functions for multi-step processing.

# Clean and format user input

raw_input = [' Hello World ', ' PYTHON MAP ', ' data science ']

formatted = list(map(lambda s: s.strip().title(), raw_input))

print(formatted) # ['Hello World', 'Python Map', 'Data Science']

# Create URL slugs

titles = ['Python Map Function', 'Data Processing Guide', 'Tutorial Examples']

slugs = list(map(lambda t: t.lower().replace(' ', '-'), titles))

print(slugs)

# ['python-map-function', 'data-processing-guide', 'tutorial-examples']

Type conversions with python map

Converting data types across collections becomes efficient with map(). You transform entire lists of strings into numbers, or vice versa, with minimal code.

# String to integer conversion

prices_str = ['10.99', '25.50', '8.75', '100.00']

prices_float = list(map(float, prices_str))

print(prices_float) # [10.99, 25.5, 8.75, 100.0]

# Integer to string conversion

codes = [404, 500, 200, 301]

code_strings = list(map(str, codes))

print(code_strings) # ['404', '500', '200', '301']

# Boolean to integer

flags = [True, False, True, True, False]

binary = list(map(int, flags))

print(binary) # [1, 0, 1, 1, 0]

Complex type transformations work through custom functions or lambda expressions. You can parse timestamps, extract numeric values from formatted strings, or convert between measurement units.

# Parse formatted currency strings

currency = ['$100', '$250', '$75']

amounts = list(map(lambda x: float(x.replace('$', '')), currency))

print(amounts) # [100.0, 250.0, 75.0]

# Convert percentage strings to decimals

percentages = ['25%', '50%', '75%', '100%']

decimals = list(map(lambda x: float(x.rstrip('%')) / 100, percentages))

print(decimals) # [0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0]

Choosing between python map and list comprehensions

List comprehensions offer an alternative syntax for transforming iterables. Both approaches achieve similar results, but each excels in specific scenarios.

Map() works best when you already have a function to apply. Passing an existing function to map() produces cleaner code than wrapping it in a list comprehension.

# Using map with existing function

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

absolutes = list(map(abs, numbers))

# Equivalent list comprehension

absolutes = [abs(x) for x in numbers]

List comprehensions become more readable when you need filtering or complex conditional logic. They also feel more intuitive to developers who primarily use imperative programming patterns.

# List comprehension with filtering

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

even_squares = [x**2 for x in numbers if x % 2 == 0]

print(even_squares) # [4, 16, 36, 64]

# Map requires filter() for the same result

even_squares = list(map(lambda x: x**2, filter(lambda x: x % 2 == 0, numbers)))

Memory efficiency matters when processing large datasets. Both map() and generator expressions use lazy evaluation, but map() can be slightly faster for simple transformations because it’s implemented in C.

# Memory-efficient with map

large_data = range(1000000)

transformed = map(lambda x: x * 2, large_data) # No memory used yet

# Memory-efficient with generator expression

transformed = (x * 2 for x in large_data) # Also lazy

Common python map patterns for data processing

Chaining map() with other functional tools creates powerful data pipelines. You can filter data first, then transform it, or transform and then reduce results.

# Filter negative numbers, then square positives

numbers = [-5, -2, 0, 3, 8, -1, 7]

positive_squares = list(map(lambda x: x**2, filter(lambda x: x > 0, numbers)))

print(positive_squares) # [9, 64, 49]

# Transform and aggregate

sales = [100, 200, 150, 300]

total_with_tax = sum(map(lambda x: x * 1.1, sales))

print(total_with_tax) # 825.0

Dictionary transformations benefit from map() when you need to process keys or values uniformly. You extract, transform, and rebuild dictionaries efficiently.

# Transform dictionary values

prices = {'apple': 1.2, 'banana': 0.5, 'orange': 0.8}

rounded = dict(map(lambda item: (item[0], round(item[1])), prices.items()))

print(rounded) # {'apple': 1, 'banana': 0, 'orange': 1}

# Convert keys to uppercase

data = {'name': 'Alice', 'age': 30, 'city': 'NYC'}

upper_keys = dict(map(lambda item: (item[0].upper(), item[1]), data.items()))

print(upper_keys) # {'NAME': 'Alice', 'AGE': 30, 'CITY': 'NYC'}

Nested iterables require map() calls at each level. You flatten structures, transform inner elements, or reshape data hierarchies.

# Transform nested lists

matrix = [[1, 2, 3], [4, 5, 6], [7, 8, 9]]

doubled = list(map(lambda row: list(map(lambda x: x * 2, row)), matrix))

print(doubled) # [[2, 4, 6], [8, 10, 12], [14, 16, 18]]

# Extract specific fields from nested data

users = [

{'name': 'Alice', 'age': 30},

{'name': 'Bob', 'age': 25},

{'name': 'Charlie', 'age': 35}

]

names = list(map(lambda user: user['name'], users))

print(names) # ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie']

Performance considerations for python map

The python map function executes faster than equivalent for loops for simple transformations because it runs optimized C code internally. This performance advantage becomes noticeable when processing millions of elements.

Map objects consume minimal memory regardless of input size because they generate values on demand. A map object processing a billion elements uses the same memory as one processing ten elements.

import sys

# Map object size stays constant

small_map = map(lambda x: x**2, range(10))

large_map = map(lambda x: x**2, range(1000000))

print(sys.getsizeof(small_map)) # 56 bytes

print(sys.getsizeof(large_map)) # 56 bytes

Convert map objects to lists only when you need all results immediately or require multiple iterations. Keeping results as map objects saves memory and often improves performance.

# Good: Process without converting to list

total = sum(map(lambda x: x**2, range(1000)))

# Wasteful: Unnecessary conversion

squares = list(map(lambda x: x**2, range(1000)))

total = sum(squares)

The python map method remains a powerful tool for functional-style data transformations. It produces clean, efficient code when you need to apply functions uniformly across iterables. Understanding when to use map() versus alternatives like list comprehensions or generator expressions helps you write more effective Python programs.