import numpy as np

# Create 5 evenly spaced values between 0 and 10

result = np.linspace(0, 10, 5)

print(result)

# Output: [ 0. 2.5 5. 7.5 10. ]

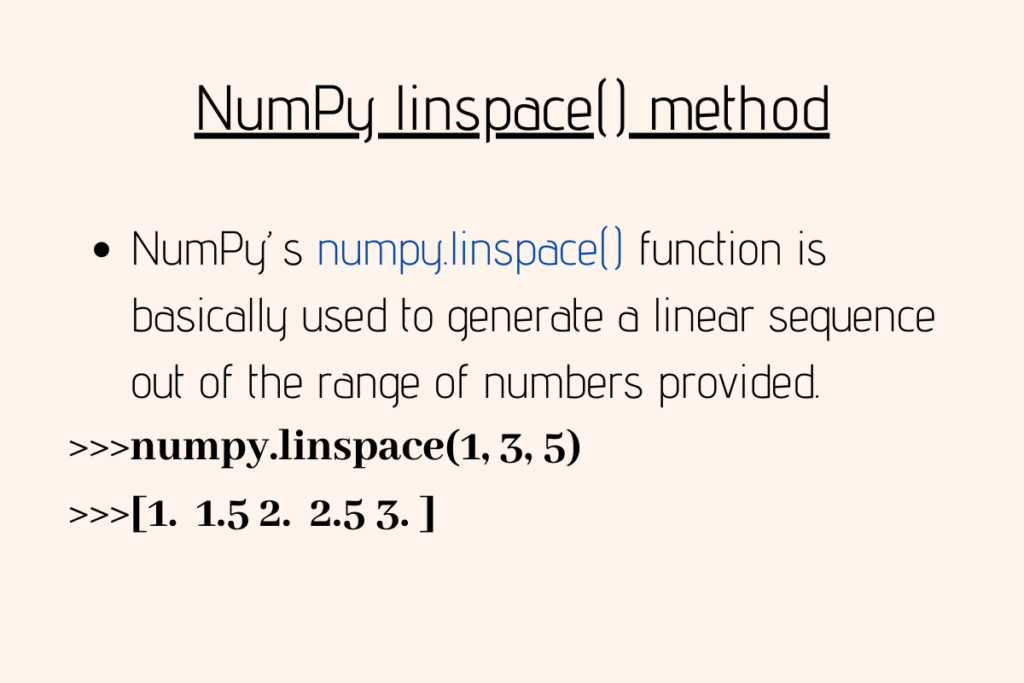

The np.linspace function generates evenly spaced numbers across a defined interval. You specify where to start, where to stop, and how many values you want. NumPy calculates the spacing automatically.

Basic syntax for np.linspace

The function accepts several parameters that control array generation:

numpy.linspace(start, stop, num=50, endpoint=True, retstep=False, dtype=None, axis=0)

The start parameter defines your first value. The stop parameter sets your last value (or the boundary if endpoint is False). The num parameter determines how many values to generate between these boundaries.

import numpy as np

# Generate 10 values from 0 to 100

values = np.linspace(0, 100, 10)

print(values)

# Output: [ 0. 11.11111111 22.22222222 33.33333333 44.44444444

# 55.55555556 66.66666667 77.77777778 88.88888889 100.]

NumPy divides the interval into equal segments. With 10 values spanning 0 to 100, each step measures approximately 11.11 units. The function includes both endpoints by default, which affects the spacing calculation.

Understanding the endpoint parameter in np.linspace

The endpoint parameter changes how np.linspace calculates spacing. When endpoint equals True (the default), the stop value appears in your output array. When endpoint equals False, NumPy excludes the stop value and adjusts the spacing.

import numpy as np

# With endpoint included

included = np.linspace(0, 10, 5, endpoint=True)

print("Endpoint included:", included)

# Output: [ 0. 2.5 5. 7.5 10. ]

# Without endpoint

excluded = np.linspace(0, 10, 5, endpoint=False)

print("Endpoint excluded:", excluded)

# Output: [0. 2. 4. 6. 8.]

Notice how the spacing changes. With the endpoint included, you get values at 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10. Without the endpoint, the spacing becomes 2.0 instead of 2.5, and the array stops at 8.

This behavior matters when you need precise control over array boundaries. For periodic functions or when creating bins for histograms, excluding the endpoint often produces cleaner results.

import numpy as np

# Creating bins for a histogram

bins = np.linspace(0, 100, 11, endpoint=False)

print(bins)

# Output: [ 0. 10. 20. 30. 40. 50. 60. 70. 80. 90.]

Getting step size with the retstep parameter

The retstep parameter returns both the array and the spacing between values. This becomes useful when you need to know the exact step size for subsequent calculations.

import numpy as np

# Get array and step size

array, step = np.linspace(0, 50, 11, retstep=True)

print("Array:", array)

print("Step size:", step)

# Output:

# Array: [ 0. 5. 10. 15. 20. 25. 30. 35. 40. 45. 50.]

# Step size: 5.0

The function returns a tuple when retstep is True. You can unpack this tuple directly into two variables, as shown above. The step value represents the distance between consecutive elements.

import numpy as np

# Using step size for calculations

values, spacing = np.linspace(1, 100, 20, retstep=True)

next_value = values[-1] + spacing

print(f"Next value in sequence: {next_value}")

# Output: Next value in sequence: 105.21052631578948

Creating arrays for plotting with np.linspace

Plotting functions requires x-axis values with sufficient resolution to show smooth curves. The np.linspace method excels at generating these coordinate arrays.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Generate x values for a sine wave

x = np.linspace(0, 2 * np.pi, 100)

y = np.sin(x)

plt.plot(x, y)

plt.title('Sine wave using np.linspace')

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.ylabel('sin(x)')

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

The code above creates 100 evenly spaced points between 0 and 2π. More points produce smoother curves but require more computation. Fewer points run faster but create jagged lines.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Compare different resolutions

x_low = np.linspace(0, 2 * np.pi, 10)

x_high = np.linspace(0, 2 * np.pi, 200)

plt.plot(x_low, np.sin(x_low), 'o-', label='10 points')

plt.plot(x_high, np.sin(x_high), label='200 points')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

You can also create custom x-axis scales for specialized plots. If your data represents temperature sensors along a conveyor belt, np.linspace generates the position values.

import numpy as np

# Position of 15 sensors from 0 to 100 meters

sensor_positions = np.linspace(0, 100, 15)

temperatures = np.random.uniform(20, 30, 15) # Random temps

for pos, temp in zip(sensor_positions, temperatures):

print(f"Position {pos:.2f}m: {temp:.2f}°C")

Evaluating mathematical functions using np.linspace

Mathematical functions operate on continuous domains, but computers work with discrete values. The np.linspace function bridges this gap by sampling functions at regular intervals.

import numpy as np

# Evaluate a quadratic function

x = np.linspace(-5, 5, 50)

y = x**2 - 3*x + 2

print(f"Minimum value: {np.min(y):.4f}")

print(f"Maximum value: {np.max(y):.4f}")

# Output varies based on sampling, but captures the function's behavior

You can combine multiple functions for complex calculations. NumPy’s vectorized operations work directly on arrays generated by np.linspace.

import numpy as np

# Calculate compound interest over time

principal = 1000

rate = 0.05

years = np.linspace(0, 30, 31) # 0 to 30 years

balance = principal * np.exp(rate * years)

print("Year 0:", balance[0])

print("Year 10:", balance[10])

print("Year 30:", balance[30])

The exponential function np.exp applies to every element in the years array. This produces a balance array showing compound growth at each time step. No loops required.

Building multidimensional arrays with np.linspace

You can transform one-dimensional linspace arrays into higher dimensions using reshape or by creating coordinate grids.

import numpy as np

# Create a 2D grid

x = np.linspace(0, 1, 25).reshape(5, 5)

print(x)

For genuine 2D coordinate systems, combine np.linspace with np.meshgrid. This creates coordinate matrices for evaluating functions of two variables.

import numpy as np

# Create 2D coordinate system

x = np.linspace(-2, 2, 50)

y = np.linspace(-2, 2, 50)

X, Y = np.meshgrid(x, y)

# Evaluate 2D Gaussian

Z = np.exp(-(X**2 + Y**2))

print(f"Grid shape: {Z.shape}")

print(f"Maximum value: {np.max(Z):.4f}")

The meshgrid function transforms two 1D arrays into two 2D matrices. Each matrix contains coordinates for evaluating functions across the grid. This technique powers 3D surface plots and contour maps.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Create saddle surface

x = np.linspace(-3, 3, 100)

y = np.linspace(-3, 3, 100)

X, Y = np.meshgrid(x, y)

Z = X**2 - Y**2

plt.contourf(X, Y, Z, levels=20, cmap='viridis')

plt.colorbar()

plt.title('Saddle surface: z = x² - y²')

plt.show()

Controlling data types with the dtype parameter

The dtype parameter specifies the data type for array elements. NumPy infers float64 by default when you provide floating-point start or stop values.

import numpy as np

# Default float type

floats = np.linspace(0, 10, 5)

print(f"Type: {floats.dtype}")

# Output: Type: float64

# Force integer type

integers = np.linspace(0, 10, 5, dtype=int)

print(f"Type: {integers.dtype}")

print(integers)

# Output: Type: int64

# [ 0 2 5 7 10]

Integer conversion truncates decimal values toward negative infinity. This can create unexpected results when you expect rounding.

import numpy as np

# Compare conversion methods

float_array = np.linspace(0, 10, 11)

int_direct = np.linspace(0, 10, 11, dtype=int)

int_rounded = np.round(float_array).astype(int)

print("Float array:", float_array)

print("Direct int:", int_direct)

print("Rounded int:", int_rounded)

You can specify any NumPy dtype: float32, complex128, or custom structured types. Lower precision types save memory but reduce accuracy.

import numpy as np

# Memory comparison

float64_array = np.linspace(0, 100, 1000, dtype=np.float64)

float32_array = np.linspace(0, 100, 1000, dtype=np.float32)

print(f"Float64 memory: {float64_array.nbytes} bytes")

print(f"Float32 memory: {float32_array.nbytes} bytes")

# Float64 uses 8000 bytes, Float32 uses 4000 bytes

Comparing np.linspace vs np.arange

NumPy provides np.arange for creating sequences with fixed step sizes. Understanding when to use each function saves debugging time.

The np.linspace function prioritizes endpoint precision. You specify exactly where to start and stop, plus how many values you need. NumPy calculates the step size.

import numpy as np

# Using linspace

lin = np.linspace(0, 1, 11)

print("Linspace:", lin)

# Output: [0. 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1. ]

The np.arange function prioritizes step size. You specify the increment between values, and NumPy generates values until reaching (but not including) the stop value.

import numpy as np

# Using arange

arr = np.arange(0, 1.1, 0.1)

print("Arange:", arr)

# Output: [0. 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1. ]

These look similar but behave differently with non-integer steps. Floating-point arithmetic in np.arange can produce unexpected results.

import numpy as np

# Arange with floating-point step

problematic = np.arange(0, 1, 0.3)

print("Arange with 0.3 step:", problematic)

print("Length:", len(problematic))

# Output might have 3 or 4 elements depending on rounding errors

Use np.linspace when you need exact start and stop values, especially for plotting or mathematical analysis. Use np.arange when the step size matters more than the endpoint, particularly with integer sequences.

Practical use cases for np.linspace in data science

Time series analysis often requires evenly spaced timestamps. The np.linspace function creates these temporal arrays for resampling or interpolation.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

# Create hourly timestamps for a day

hours = np.linspace(0, 24, 25)

timestamps = pd.date_range('2024-01-01', periods=25, freq='h')

# Simulate temperature readings

temperatures = 20 + 5 * np.sin(2 * np.pi * hours / 24)

df = pd.DataFrame({

'timestamp': timestamps,

'temperature': temperatures

})

print(df.head())

Machine learning models sometimes need synthetic data for testing. You can generate evenly distributed features using np.linspace.

import numpy as np

# Generate synthetic linear regression data

X = np.linspace(0, 10, 100).reshape(-1, 1)

noise = np.random.normal(0, 1, 100).reshape(-1, 1)

y = 3 * X + 5 + noise

print(f"Feature shape: {X.shape}")

print(f"Target shape: {y.shape}")

Signal processing applications use np.linspace to create time arrays for sampling continuous signals at specific frequencies.

import numpy as np

# Sample rate of 44.1 kHz (CD quality)

sample_rate = 44100

duration = 1.0 # seconds

# Create time array

t = np.linspace(0, duration, int(sample_rate * duration), endpoint=False)

# Generate 440 Hz tone (musical note A)

frequency = 440

signal = np.sin(2 * np.pi * frequency * t)

print(f"Signal length: {len(signal)} samples")

print(f"Signal duration: {duration} seconds")

The endpoint=False parameter prevents creating a sample at exactly 1.0 seconds, which would duplicate the start of the next period in continuous playback.

Common patterns and edge cases with np.linspace

Single-value arrays serve as edge cases. When num equals 1, np.linspace returns the start value.

import numpy as np

single = np.linspace(5, 10, 1)

print(single)

# Output: [5.]

Empty arrays result from num=0. This creates a valid NumPy array with zero elements.

import numpy as np

empty = np.linspace(0, 10, 0)

print(empty)

print(f"Length: {len(empty)}")

# Output: []

# Length: 0

Negative ranges work identically to positive ranges. The function simply creates evenly spaced values in reverse order.

import numpy as np

negative = np.linspace(10, 0, 11)

print(negative)

# Output: [10. 9. 8. 7. 6. 5. 4. 3. 2. 1. 0.]

Complex number ranges follow the same logic, spacing values in the complex plane.

import numpy as np

complex_range = np.linspace(0+0j, 1+1j, 5)

print(complex_range)

# Output: [0. +0.j 0.25+0.25j 0.5 +0.5j 0.75+0.75j 1. +1.j ]

The np.linspace function handles these edge cases consistently. The same spacing algorithm applies regardless of value types or ranges.

Performance considerations for np.linspace arrays

Large arrays consume memory proportionally to their size. A million-element float64 array requires about 8 megabytes.

import numpy as np

# Create large array

large = np.linspace(0, 1, 1_000_000)

print(f"Memory usage: {large.nbytes / 1024 / 1024:.2f} MB")

# Output: Memory usage: 7.63 MB

Generation speed scales linearly with array size. Creating 10 million elements takes roughly 10 times longer than 1 million elements.

import numpy as np

import time

sizes = [1_000, 10_000, 100_000, 1_000_000]

for size in sizes:

start = time.time()

arr = np.linspace(0, 1, size)

elapsed = time.time() - start

print(f"Size {size}: {elapsed*1000:.4f} ms")

For extremely large arrays, consider generating values on demand rather than storing everything in memory. Generator expressions or chunked processing save resources.

The np.linspace method remains one of NumPy’s most versatile functions. It creates evenly spaced arrays for plotting, mathematical analysis, signal processing, and scientific computing. The function’s simplicity conceals its power. You specify boundaries and count, and NumPy handles the rest. Master this function and you unlock precise numerical control across countless applications.