for index, value in enumerate(['apple', 'banana', 'cherry']):

print(f"{index}: {value}")

# Output:

# 0: apple

# 1: banana

# 2: cherry

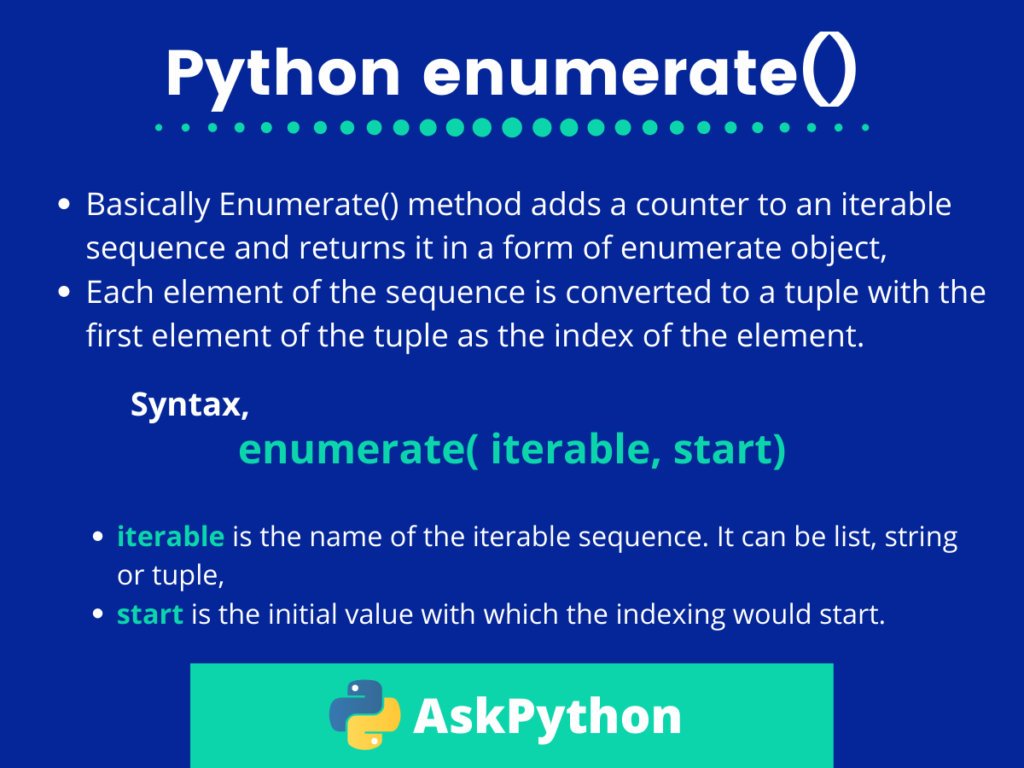

That’s Python enumerate() in its most basic form. It takes any iterable and returns both the index and the value at each iteration.

The syntax is enumerate(iterable, start=0), where start is optional and defaults to zero.

Why enumerate exists in Python

You could write a counter yourself. You’ve probably done it a thousand times, incrementing some variable by one on each loop iteration. But that’s the kind of boilerplate that makes code harder to read and easier to mess up. Python’s enumerate() removes that friction entirely.

The function returns an enumerate object (technically an iterator) that yields tuples containing (index, value) pairs. You unpack these tuples directly in your for loop, which keeps the code clean and the intent obvious.

# The old way (don't do this)

index = 0

for item in my_list:

print(f"{index}: {item}")

index += 1

# The enumerate way

for index, item in enumerate(my_list):

print(f"{index}: {item}")

The difference matters more than you’d think. That manual counter approach introduces a variable you have to track, remember to increment, and keep in scope. It’s one more thing that can break.

Starting enumerate at custom index values

The second parameter to enumerate() lets you specify where counting begins. This solves the incredibly common problem of displaying human-readable numbered lists that start at 1 instead of 0.

tasks = ['Write code', 'Test code', 'Ship code']

for number, task in enumerate(tasks, start=1):

print(f"{number}. {task}")

# Output:

# 1. Write code

# 2. Test code

# 3. Ship code

You can start at any integer. Negative numbers work too. This becomes useful when you’re processing subsets of data but need to maintain original index positions.

data = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e']

subset = data[2:] # ['c', 'd', 'e']

for index, value in enumerate(subset, start=2):

print(f"Original index {index}: {value}")

# Output:

# Original index 2: c

# Original index 3: d

# Original index 4: e

Using enumerate with conditional logic

Combining enumerate() with conditionals gives you powerful filtering capabilities while preserving index information. You can find positions of specific elements, track where certain conditions occur, or build mappings based on position.

numbers = [10, 25, 30, 15, 40, 35]

high_values = []

for index, num in enumerate(numbers):

if num > 20:

high_values.append((index, num))

print(high_values)

# Output: [(1, 25), (2, 30), (4, 40), (5, 35)]

This pattern shows up constantly in data processing. You need to know not just what matches your criteria, but where it appears in the sequence. List comprehensions work here too, keeping the code even tighter.

high_indices = [i for i, num in enumerate(numbers) if num > 20]

# Output: [1, 2, 4, 5]

Enumerating multiple iterables with zip

When you need to iterate over multiple sequences simultaneously while tracking position, combining enumerate() with zip() creates a clean solution.

names = ['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie']

scores = [85, 92, 78]

for index, (name, score) in enumerate(zip(names, scores)):

print(f"Rank {index + 1}: {name} scored {score}")

# Output:

# Rank 1: Alice scored 85

# Rank 2: Bob scored 92

# Rank 3: Charlie scored 78

The nested unpacking (name, score) pulls values from the tuple that zip() creates, while index comes from enumerate(). You get position, name, and score all in one loop header.

Modifying lists during enumeration

One mistake that trips people up: trying to modify a list while iterating over it with enumerate(). The enumerate object doesn’t care if you change the underlying list, but the results get weird fast.

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

# This will skip elements

for index, num in enumerate(numbers):

if num % 2 == 0:

numbers.pop(index) # Don't do this

# Instead, enumerate a copy or build a new list

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

filtered = [num for i, num in enumerate(numbers) if num % 2 != 0]

If you absolutely need to modify in place based on index, iterate backwards or collect indices first, then modify separately. The cleaner approach is usually to build a new list.

Performance characteristics of enumerate

The enumerate() function is memory efficient because it returns an iterator, not a list. It generates index-value pairs on demand as you loop, which means it works identically whether you’re processing 10 items or 10 million.

# This doesn't create a huge list in memory

for i, line in enumerate(open('massive_file.txt')):

if i > 1000000:

break

process(line)

Compare this to manually creating index-value pairs with something like list(zip(range(len(items)), items)). That approach builds the entire structure in memory before iteration starts, which wastes space and time.

Real-world enumerate patterns

Database result processing often needs both the row position and the row data. Enumerate handles this perfectly when you’re validating data, tracking errors by line number, or building batch operations.

# Processing CSV data with error tracking

rows = [

{'name': 'John', 'age': '30'},

{'name': 'Jane', 'age': 'invalid'},

{'name': 'Bob', 'age': '25'}

]

errors = []

for row_num, row in enumerate(rows, start=1):

try:

age = int(row['age'])

except ValueError:

errors.append(f"Row {row_num}: Invalid age '{row['age']}'")

# Output: ["Row 2: Invalid age 'invalid'"]

Web scraping and API pagination benefit from enumerate when you need to track which page or batch you’re on while processing results. The index becomes your page counter, your retry key, or your checkpoint for resuming interrupted operations.

# Batch processing with progress tracking

api_responses = fetch_all_pages()

for batch_num, response in enumerate(api_responses):

print(f"Processing batch {batch_num + 1} of {len(api_responses)}")

process_batch(response.data)

if batch_num % 10 == 0:

checkpoint_progress(batch_num)

The key insight with enumerate() is that it removes mechanical complexity from a pattern you use constantly. You’re not fighting the language to track position. You’re just stating what you need, and Python delivers it cleanly. That’s what good abstractions do. They make the common case trivial so you can focus on the logic that actually matters.